Ballad of the Tall Submariner

Jul.30,2023

Jul.30,2023People ask me often, upon learning I’m a submariner, “Aren’t you too tall for Submarines?”

My usual reply is to joke that I was 6’8” when I started (4” taller than my actual height)

Look, I’m not saying it wasn’t problematic at times. Heck, I even started an actual ballad once. Went like this:

(Ahem) “Ballad of the tall submariner

“Down the hatch, Down the ladder,

Bash the head and see brain cells scatter.”

And so it was, at the bottom of the main hatch of the USS Shark, SSN-591, I turned to see my new home. It left an impression.

On my right temporal lobe, specifically. It was the most solid thing I’d ever felt.

Being a nub, I had no idea what I’d just clocked my cranium on. And therein lay the beauty of the Submarine qualification program. I would soon be able to identify every single head trauma by ship’s frame, subsystem, associated components, function, and nomenclature. It would also teach me many new terms, some technical, some… well, some were just eloquent expressions developed in a climate ripe for salty diatribes. New words for new levels of pain.

It still hurt though.

My first destination was the ship’s office. Maybe 20 steps through control and the upper level passageway – past Sonar, past Supply, across from Radio. In those 20 steps, I found the following: two battle lanterns, two vents, two pipe mounting brackets (the hard way). There may have been more, the last few steps were getting a little fuzzy.

In somewhat of a boxer’s daze, I took a hard draft reading of the ship’s office door, height from the deck. It stood approximately 6’2”. I was 6’4”. My forehead remembers that reading precisely, to this day, and little else after.

The first underway was the next morning. I met what would become my defining nemesis shortly. But first, I hit the torpedo room/crews mess watertight door and softened up the back of my head. The opening was maybe 3’ tall, and I thought I’d try to fold forward and hope I was flexible enough to get my head and feet through at the same time. I would soon learn to go feet first whenever possible.

But immediate problems demanded immediate attention. Still rubbing the back of my skull, I discovered The Vent. It was in the crews mess – the one that protruded only an inch or so from the overhead, and painted to match (which is how everything gets painted on a submarine). It’s edge caught me well up into the hairline with absolutely no warning. I rocked back a bit, and re-adjusted. And sat down a moment on one of the benches.

Whereupon someone asked me where my qual card was, and why was I sitting and not working on it. I failed to notice the entire room’s attention suddenly focused on what my answer to this ungentle challenge would be.

I tried not to glare. I knew better. But the glaze in my eyes was misinterpreted as petulance. Ok, maybe it WAS petulance, but the attention was also a trap, set, coiled, and waiting for me. Sensing a tedious discussion, I stood back up, smug about having avoided an outburst, only to hit the same vent in the same spot.

I managed finally to stagger clear of the galley, only to bump-test a pipe at the top of the ladder to lower level. In my own head, the impact seemed to say, “Clang!” It would evolve into an entire battery of internal sound effects, some of which I would actually utter out loud at times. This would prove in a few moments to be a bad idea.

It happened again on returning to the torpedo room, this time on the starboard torpedo ram handle that sat waiting for someone just over 6’2” to duck through the watertight door NOT feet-first, and in a hurry. There really was a “clang” that time, and may have been a couple minutes downtime on my part. It happened again while avoiding the head valve in ops upper level. It happened in AMRLL. It happened in Shaft Alley. It happened in LL Berthing. Always, in my head, I heard and said, “Clang”. And I moved on.

In a couple short weeks of underway, I had memorized the overhead layout of the boat faster than anything else. I developed the skill of sensing impact with my hair, reflexively preventing the worst of impacts. As I would navigate a passage, my head would flop and bend like a curb feeler on a Chicago Cadillac. The first few days’ worth of damage had begun to heal, and my qual card began to fill out with signatures. I began to walk with a little confidence. I walked a little straighter, as it hurt to hunch constantly, letting my neck control my destiny. I’m sure it looked goofy, but it worked. Mostly.

And so it was that I came to be gliding through the crew’s mess again one fine day, intent on my task at hand. With a full head of steam, I spectacularly failed to duck for The Vent as I strode through towards the Torpedo room. What happened next is a little fuzzy, but there was a “clang” that wasn’t mine. I was busy holding my head from the gritty impact on the Vent of Despair, which had set me down on a bench again, so someone took the liberty of saying it for me. In my misery, I burst out with some sailor-ish vulgarity I had just recently mastered, signaling to the ever-attentive crew that I’d reached some sort of emotional limit. Suddenly the entire space erupted in enthusiastic chorus of “Clang!”

And thus for many weeks, I endured being known simply as “Clang”. The name lasted through my time of qualifying. As a Sonarman, I couldn’t think of a more ignominious nickname.

Eventually I managed to live the whole thing down. But to this day, when I whack something with my head, that little voice yells “CLANG” in my head. And it’s not my voice. It a chorus of shipmates, who understand. They are with me still.

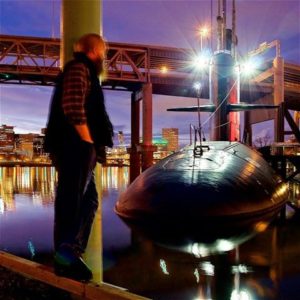

Photo: USS Razorback, SS-394, 2022. ©️Glenn Roesener

Filed Under :

Filed Under :

Tags :

Tags :